by: Kwame Opoku

For many of us, the name Ekpo Eyo has come to stand for excellence and erudition. The first Director-General of the Nigerian Commission for Museums and Monuments, has produced several articles and books of the highest quality on Nigerian art, and his recent book, From Shrines to Showcases: Masterpieces of Nigerian Art, (2010, Federal Ministry of Information and Communication, Abuja) is no exception. It is a masterpiece in its own right.

After an introduction to Nigerian art that gives the historical background of the arts and archaeological art, the introduction deals with accounts of discoveries and examines issues in the preservation and conserving of Nigerian cultural heritage. I enjoyed thoroughly Eyo's discussion on what art is and the early Western views of African art as well as the topic of primitivism, tribality and universalism:

“What is a work of art and how does one know when seeing one? There are certain concepts in the world that are difficult to define and art is certainly one of them. This is clear from the study of the global history of art because what may be regarded as art in one society may not be so regarded in another. Moreover, a particular definition of art may not be universally accepted even within the same community or scholarly field or local art scene.” (p.13) What distinguishes a work of art from a merely functional object is “The special attention to character and the lavishing of imagination on individual artworks, rather than mass produced items, was what became known as aesthetics - which was ill defined - but nonetheless was seized upon by connoisseurs of Western art as the criterion for good art.”(p.13).

Veranda post, equestrian figure, carved by Areogun of Osi-Ilorin National Museum, Lagos, Nigeria.

Aesthetics then distinguishes artworks from other utilitarian objects. The failure to understand this fact explains why it took so long, until 20th century for many in the West to accept African art as art. Even today, in the 21st century, there is still a need to persuade many that African art addresses aesthetic concerns. Ekpo points out that following Darwin's theory of evolution, human societies were classified into three stages: the age of savagery, the age of barbarism, and the age of civilization. The Europeans who made this classification, put ancient Greeks and Romans into the age of civilization but all non-Western people were thrown to the bottom of the scale: “It is ironic that ancient Egypt was considered a precursor to Western civilization and, therefore not really “African” despite the simple fact that it actually developed in Africa”.(p.15).

Eyo recalls that the word “civilization” is of relatively recent usage and that Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), originator of the famous Dictionary of the English Language declined in 1772 to include “civilization” in this work. The word came into general use by the time of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of nationalism in Europe and North America. From then on the world was divided by the Europeans into the “civilized” and the “savage.” Those from the West were civilized and those from the rest of the world were savages. Eyo states that: “It became the duty of anthropologists, travellers, explorers and missionaries to spread these ideas wherever they went, and to redeem the God forsaken people they encountered.” (p.16)

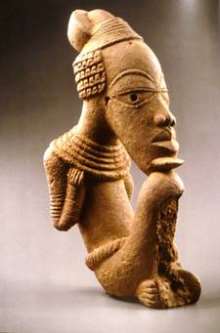

Figure of a seated male. One of the looted Nok terracotta bought by the French, now in the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France, with Nigerian post factum consent.

The dichotomy between “civilized” and “savage” was as may be expected, applied in the field of art. Europeans classified all-non Western art as “primitive” because in their view true art could only be made by Western peoples. Explorers who came to Africa took home African works out of curiosity to show to their people that they had been to the land of the primitive people. The missionaries gathered African objects to deprive Africans of what they considered to be the focus of their worship and show Europeans that these were idols. Colonial administrators took artefacts as proof of the backwardness of people whom they had to bring civilization. The anthropologists considered African objects as ethnographic objects of primitive people. None of the above-mentioned groups of European regarded the African objects as works of art. One anthropologist cited by Eyo, Leonhard Adam, stated that “Actually they are not so much works of art as failed attempts to produce on.”(p. 16) The European prejudice about African art was so engrained that as late as 1959, the famous art historian Ernst Gombrich asked an American professor “Is there African art?” When told that there exists African art, Gombrich objected : To be sure there are those who speak of “ primitive art although I do not find it proper to use the term “art” where one is referring to simple shapes used for the building up of different representation. (p.17)” Gombrich, who had seen the exhibition Treasures of Ancient Nigeria Legacy of 2,000 Years,co-curated by Ekpo Eyo, had been “Overwhelmed” by Ife and Benin bronzes. But when asked whether these works qualified as works of art, said “yes” but then asked his interlocutor, “Do you really believe that the Ife and Benin pieces were the work of Africans?” (p.18)

William Fagg who had visited Nigeria several times did not like the term “primitive” and replaced it by the term “tribal”. He identified specific art works with specific tribes and declared that what is not tribal is not African. As may be expected, Ekpo Eyo, objects equally to the term “tribal “ as misleading since it denies statehood to well organized states such as those of the Asante, the Yoruba, the Edo, the Kongo and the Kuba and suggest that there had been no cultural exchanges among African societies and influences from one society to the other. It also creates the impression that there is a specific style for a specific people. Eyo discusses Nok culture and expresses regret that “they have been looted over time to supply the international market. Properly excavated, such pieces might have shed valuable light on Nok culture.” (p.23) The author is very polite and does not mention that some of the looted Nok pieces ended up in Paris, Musée de quai Branly as his catalogue of works clearly show.

read more>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>