By:Denmark Vesey

Controversy continues to swirl around efforts to erect a monument toDenmark Vesey in Charleston, South Carolina, the former slave of a Bermudian sea captain who was executed for plotting a slave rebellion in the city in 1822.

One hundred and fifty years after the opening shots in the American Civil War were fired by Confederate forces on Fort Sumter in Charleston, the city remains divided over its history of slavery. The debate centres around the legacy of Denmark Vesey — who is thought to have visited Bermuda a number of times and spent some of his early life on the island before his seagoing master, Captain Joseph Vesey, settled in Charleston.

Local black activists first proposed the tribute in the 1990s so that the city would acknowledge the centrality of slavery to its past. They also hoped the Vesey monument would force Charlestonians to confront the reality that slaves were unhappy, so much so that they might violently rebel.

Resistance to the monument has been formidable. Some whites have offered a litany of excuses about the marginal role, and “benign nature”, of slavery in South Carolina. Ground on the memorial was finally broken in February 2010, but only after opponents had prevented the statue’s placement in downtown Marion Square.

Instead the Denmark Vesey Memorial will stand in Hampton Park, far from the city’s historic district, far from the eyes of millions of tourists.

The design, by Colorado artist Ed Dwight, features a seven-foot Vesey with a Bible and carpentry tools. It’s hoped work will be completed on the memorial within the next year.

Charlestonians have debated for decades about preserving the memory of Denmark Vesey with any sort of monument. For generations, many of Charleston’s whites typically believed Mr Vesey to be a ruthless would-be mass murderer, while many blacks saw him as a hero, a martyr in the fight against the great injustice of slavery. During the Civil War, Frederick Douglass repeatedly invoked the name of this Bermudian’s slave while recruiting the black troops who would ultimately turn the tide against the Confederacy.

Nearly ten years ago, when the Charleston City Council first appropriated funds to erect a statue of Mr Vesey, controversy instantly erupted. The local newspapers were flooded with letters from readers, many appalled at the idea of memorializing a man one called an “advocate of ethnic cleansing” and another “a mass murderer.” One reader called Mr Vesey’s planned rebellion “nothing less than a Holocaust,” a local talk radio host complained about honoring “the guy who wanted to kill all the white people,” and he has been called a “ terrorist.”

No paintings of Denmark Vesey exist, nor is there even a known physical description of him. Little is known about his life as a slave or later, as a free man, and even the notion that in 1822 he organized what was to have been the largest and most elaborate slave insurrection in US history is a matter of some historical dispute.

And the very dearth of certain facts about this remarkable figure serves as a sort of metaphor for the experience of slavery in America: white people feared the acquisition of power by blacks — seeing it when it sometimes might not have even been there – and did whatever they could to suppress the possibility.

At the same time, white arrogance and disdain of blacks was so strong as to see no value in recording the words or actions of a black man, or even to describe his appearance.

No slave – even one of extraordinary talent and good fortune like Mr Vesey – was thought to be remarkable enough to merit an account at the time. Only a handful of certain facts about the man exist and historical context and hearsay must fill in gaps. Though he was highly literate, Vesey seems not to have kept any record of his own life, or else it’s been lost over the years.

Much of what is known about Mr Vesey has been woven together by historians who’ve closely examined the record of Vesey’s trial and from the forced testimony against him by slaves. After almost 200 years, the truth about Denmark Vesey and his alleged insurrection remains both elusive and controversial.

Almost as little is known about Captain Joseph Vesey as is known about his former slave. He was born in Bermuda, where large sugar plantations and black slave populations were fewer than in the tropics. Joseph Vesey worked as a slave ship captain for at least 13 years, stopping at slave markets in Barbados, South Carolina, Haiti, and possibly West Africa.

In 1781, Captain Vesey bought a 14-year-old slave in the Caribbean, on what is now St. Thomas in the former Danish Virgin Islands, to sell with 390 other slaves to buyers on the French colony of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti).

The boy said his name was “Telemaque,” or Capt. Vesey may have named him that; Telemachus was the son of Odysseus in Greek mythology.

Decades later, at his trial, testimony would recall how Captain Vesey and other officers admired the boy’s beauty and intelligence and therefore bequeathed him certain privileges. Their sentimental attachment to him ended, though, when he was left to do hard labor on sugar plantations at Cape Francis.

Three months after arriving there, though, Telemaque effectively forced Mr Vesey to buy him back from his owner because he suffered from “epileptic fits.” Mr Vesey refunded the plantation owner’s money, made Telemaque his personal assistant, and, perhaps not surprisingly, Telemaque never suffered another seizure.

For two years, Telemaque, who had a facility for languages, worked as an interpreter and assistant to Joseph Vesey in his slave-trading business, a position which afforded him some authority and protection.

When the captain retired, settling in Charleston, Telemaque was his slave for 17 years. After winning $1,500 in a lottery in 1799, Telemaque was able to buy his freedom on January 1, 1800 for $600. With the remaining money, he was also able to set up a carpentry business.

Captain Vesey’s motivation for allowing his release is unknown; he may have been somewhat sympathetic– he had other freed blacks living in his home – or he may have simply needed the cash.

As a free man, Telemaque chose Vesey for his surname, and, perhaps because he was born in a Danish Colony, Telemaque became Denmark.

In 1822, Mr Vesey was 55 years old. Very little is known about what fueled Mr Vesey’s change from a relatively prosperous free carpenter into the organizer of what was to be the largest slave rebellion in the history of the US.

In 1790, freedmen in Haiti, inspired by the French Revolution, petitioned the National Assembly for full citizenship. They were refused, and violence broke out, culminating in a revolt by almost half million slaves in 1791. Many whites fled to Charleston, and Capt. Vesey was treasurer of a group which raised funds to support the refugees from Haiti.

The Haitian slave revolt is thought to have been a source of inspiration to Mr Vesey, as were the appalling circumstances of the slave trade in which he was once compelled to engage as Captain Vesey’s interpreter. Historian and author David Robertson speculates that Mr Vesey’s “doctrine of negritude” may have come from the observation that black slave traders, who were complicit with white slave ship captains, could have, instead, curtailed the trade. Furthermore, “Vesey’s later insistence upon the genocide of all whites at Charleston” may have resulted from “the atrocities by whites he had witnessed” as a young man.

Mr. Robertson also believes Mr Vesey’s personal freedom and success were not satisfying to him because of the degree of spiritual autonomy he found in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He goes on to identify Mr Vesey as a spiritual and political leader whose views were a precursor to modern Black Theology.

For the purposes of the rebellion, Mr Vesey was said to have portrayed himself as the black Messiah, recruiting thousands of slaves and black freedmen by appealing to their negritude and religion. The judges in the case against Mr Vesey later wrote that ”Every principle which could operate upon the mind of man was artfully employed” to recruit fellow rebels. ”Religion, hope, fear, and deception were resorted to as the occasion required.”

In 1816, free blacks from five states met in Philadelphia and formed the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1818, Charleston’s first A.M.E. Church was built, co-founded by Mr Vesey, and in June of that year, it was temporarily shut down by white authorities. 140 freemen and slaves were arrested for violating city ordinances by worshipping after sunset. It was shut down again in 1821, and the City Council warned Rev. Morris Brown against allowing classes at the church to become “schools for slaves.” Mr Vesey’s intense anger at these closings is also thought to have fueled his desire for the insurrection.

For nearly 200 years, it was assumed by most that Mr Vesey did head up a failed rebellion, though his prosecution was based on hearsay and coerced testimony and little or no hard evidence. In the 1960s and as recently as 2001, however, there was speculation by some historians that the insurrection was merely a construct of white politicians, jockeying for power and seeking to tamp down potential rebellion.

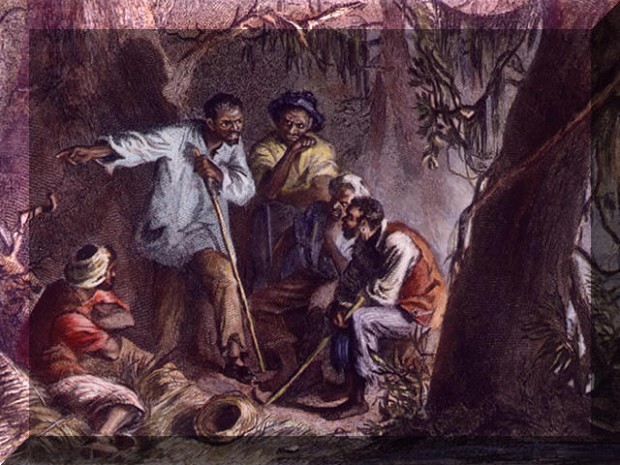

Conventional historical wisdom posits that Mr Vesey did indeed plan an insurrection (a contemporary depiction of the plotters clandestinely meeting appears below) which, if successful, would have had a radical impact on US history. Most white people in 1822 Charleston certainly believed the planned rebellion was real.

In the 1820s, South Carolina was the only state with a black majority. In Charleston — at the time the third biggest American city — slaves outnumbered whites by more than 3 to 1. In the 1800 US census, Charleston reported a population of 18,768 whites and 63, 615 blacks.

Not surprisingly, the white minority was terrified by the idea of slave rebellion and sought to protect themselves at every turn. The whites’ fear of a slave revolt led them to create a context in which such a revolt was virtually inevitable.

The eight to nine percent of the white population of Charleston that controlled its wealth created a veritable police state. For example, in addition to strict night time curfews, slaves were not allowed to appear during daylight hours wearing good clothes, smoking cigars, playing an instrument, or carrying a walking stick. Consequences for violation were severe. In 1820, a law was passed that forbade masters from freeing their slaves without first getting permission from the assembly.

Vesey’s insurrection was to include a wide-ranging combination of slave and freedmen groups: Muslims, members of Charleston’s African Methodist Church, French-speaking slaves brought to Charleston after the successful Haitian rebellion in 1791, Angola-born slaves, and those who spoke Gullah (a blend of English and African languages spoken in coastal South Carolina and Georgia).

Vesey surely utilised his multi-lingual skills as he spent four years teaching slaves to fight for their freedom. He compared them to the enslaved Israelites of the Bible, and repeated the anti-slavery arguments made in the “Missouri Compromise” bill.

Estimates as low as “several” thousand and up to nine thousand slaves in Charleston, its vicinity, and remote plantations, as well as, it’s agreed, a large number of whites, were to attack with weapons such as daggers, using military precision.

According to trial testimony – again, much of it coerced through threats and torture — Vesey’s plans would have ordered the arsenal and ships at Charleston harbor seized, the city burned, and the entire white population murdered, including women and children. Sea captains were to be spared so they could take the rebels to Haiti or Africa.

On May 30, 1822, slave Peter Prioleau overheard rumours of a planned insurrection and revealed this to his master. William Paul was arrested and placed in solitary confinement, where he was supposed to have implicated Peter Poyas and William Harth. When arrested, Poyas and Harth laughed about their alleged involvement in any plot, which convinced the authorities of their innocence, so they were released but put under surveillance.

Two weeks later, another slave, George Wilson, told his master he had heard about a plot from slaves in Governor Bennett’s household. The next day, Bennett ordered the arrest of the four accused plotters.

June 16, the night the insurrection was rumored to begin, most white Charlestonians fearfully kept watch, despite authorities’ efforts to keep the discovery of the plot quiet. Three days later, the first trial began.

Paul, who had remained in solitary confinement for weeks and had been threatened with hanging, was the mostly likely implicator of Mr Vesey as the leader of the insurrection. Mr Vesey was found hiding in his second wife’s home and was arrested June 22; his trial began four days later.

Though there was little or no physical evidence to implicate them, 131 people were charged with conspiracy, 67 men were convicted and 35 hanged, including Denmark Vesey.

Mr Vesey’s performance in court is as shrouded in contradiction and the absence of concrete fact as nearly everything else in his story. On the one hand, he is said to have rather brilliantly cross-examined witnesses and made a compelling final plea to the court. Other accounts claim he was never allowed to speak on his own behalf or confront his accusers.

There are two historical records of the trial. One major source is raw trial transcripts, on file at the State Archives in Columbia, South Carolina, which are essentially just a collection of notes from the interrogation of witnesses and show no cross examinations. These copies were probably edited and presented as part of Governor Bennett’s official report to the General Assembly in the fall of 1822.

Another source, found after the Civil War, is a pamphlet detailing the judges’ version of events. “The Official Report of the Trials of Sundry Negroes Charged with an Attempt to Raise an Insurrection in the State of South Carolina” may have been privately published to defend their actions against some public criticism.

This “Official Report” by the judges adds some testimony that is not in the raw transcript and omits other testimony such as an alleged poisoning scheme. The judges make no secret of of the fact that many witnesses were coerced to testify by solitary confinement, beatings, and threats of execution. The judges unapologetically stated that their proceedings departed “in many essential features from the principles of common law.”

No trial coverage appeared in the newspapers, only a notice of the executions and an editorial defending the judges’ integrity. Charleston resident and Associate US Supreme Court Justice William Johnson raised anonymous questions about the legality of the trials in The Charleston Courier.

Efforts at insurrection did not end with Mr Vesey’s arrest. On the day of his execution, two brigades of troops –- on guard day and night – were required to deter rebellious blacks from action. Foreseeing that slaves would continue to seek opportunities to organise and rebel, US troop re-enforcements were sent in August to guard against a renewal of the insurrection.

On July 2, Denmark Vesey and six others were hanged at dawn. Twenty-eight additional hangings followed, some botched, which necessitated the shooting of the condemned. One prisoner died in prison, and thirty-seven slaves alleged to be plotters were transported outside the state. Twenty-three slaves were acquitted, and three, though they were found not guilty, were still whipped for their suspected involvement. Four white men were also given short prison sentences for making statements sympathetic to the accused.

Later that year, the State Legislature would compensate masters with awards of $122.86 for each of their executed slaves.

By the Fall, leaders of the black AME Church were forced to flee the state. The AME congregation was said to have “voluntarily dispersed,” so authorities razed the building.

Governor Thomas Bennett’s official report to the legislature criticized the court since there was “no persuasive evidence that a conspiracy in fact existed or at most it was a vague and unfortunate plan in the minds or tongues of a few colored townsmen.”

Bennett asked State Attorney General Robert Y. Hayne for his opinion on the legality of the trials. Hayne replied that: “Magna Charta and Habeas corpus do not apply (to slaves) and indeed all the provisions of (the) Constitution in favor of liberty are intended for (white) freedmen only.”

On May 20, 1835, Captain Joseph Vesey died at 88, leaving no record of his thoughts about his former slave or the alleged insurrection.

Recently questions have arisen about whether or not the slave rebellion plot Mr Vesey was convicted of leading even really existed. Michael Johnson, a historian at Johns Hopkins University, wrote a scholarly article in 2001 which is to become a book. Johnson posits that the insurrection conspiracy that led to Vesey’s execution was a fabrication — a white politician’s ploy to discredit a rival — and the effort was abetted by the torture-induced testimony of terrified slaves.

Even apart from Mr. Johnson’s ideas, Mr Vesey’s legacy remains controversial in Charleston. For example, in 1976, the City of Charleston hung a painting of Mr Vesey by Dorothy B. Wright (pictured below) in the lobby of its Gaillard Municipal Auditorium. But soon after its unveiling, someone stole the portrait, tossing it into the bushes outside the auditorium. The portrait is now firmly bolted in place.

Henry Darby, an African-American social studies teacher, and now a member of Charleston’s county council, believes Mr Vesey –- who is buried in an unmarked grave in an unknown location –- is an important historical figure and deserves a monument. In a city with what some might call an obsessive interest in its own history, Mr. Darby feels, there are no memorials to the blacks who built the city.

Once outnumbering whites by more than three to one, blacks and their leaders languish unremembered, while statues remain for proponents of slavery. “From an educational perspective,” Mr. Darby says, Denmark Vesey’s story “is a point of history, so it needs to be told.”

Mr. Darby says this is a misinterpretation of the point of Mr Vesey’s rebellion, which he says was known to have had large numbers of white supporters. Mr Vesey and his people intended not to massacre whites for the sake of revenge or sport but “to escape, to get away” from enslavement by any means necessary.

But the focus remains for many on the aspect of Mr Vesey’s plot that sealed the conspirators’ fates at their trials. As recently as April 2006, Citadel history professor Kyle Sinisi was quoted in Charleston’s “City Paper” as saying, “I’m not a fan of applying our values of today to the past; this is cherry-picking history.” In the 1820s, Mr. Sinisi points out, many black freedmen owned slaves, and slavery lacked the “stigma” attached to it today. He believes the desire to memorialise Mr Vesey stems from an “obsession with race,” and feels “not overly enthusiastic about erecting a monument to a man bound and determined to create mayhem.”

In October 2001, Johns Hopkins University historian Michael Johnson claimed that Mr Vesey and his alleged co-conspirators were the victims of ambitious Charleston Mayor James Hamilton Jr., who created a false conspiracy in order to advance himself politically against South Carolina Governor Thomas Bennett, Jr. Bennett owned four of the first men arrested and charged with plotting rebellion.

Mr. Johnson’s conclusions first appeared in the “William and Mary Quarterly”, a prestigious journal of early American history. He is set to release a book on the subject soon.

Hamilton was known to have supported a militant approach to protecting slavery, in opposition to the recently developed Missouri Compromise, which allowed the US Federal government to restrict slavery in the West. Mr. Johnson posits that Hamilton wanted to discredit the more moderate Bennett and advance his own career, so with the support of other white authorities, he concocted the plot and enlisted the assistance of a kangaroo court.

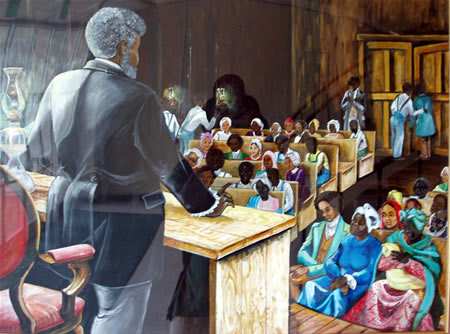

Given the disproportionate ratio of blacks to whites and the terrible circumstances in which blacks lived (a contemporary engraving of a Charleston slave auction in the 1820s is shown below), it was not difficult for everyone, black or white, in South Carolina at the time to believe that there was indeed a conspiracy. Even Governor Bennett, who thought Hamilton might be exaggerating the extent of Mr Vesey’s plot, still called the plan “a ferocious, diabolical design.”

Of great importance to Mr. Johnson’s argument is the fact that Mr Vesey and the others convicted of the conspiracy never admitted their guilt. Mr. Johnson also noted that most if not all of the “evidence” against Mr Vesey was largely coerced from slaves who had been tortured, placed in solitary confinement, and offered protection from prosecution if they would name “conspirators.” (Despite extensive torture, 90 percent of the incriminating testimony in the deadliest phase of the trials came from only six slaves, Mr. Johnson found.)

Most of the evidence for Mr. Johnson’s revisionist views comes from the transcripts of the court proceedings, which differ greatly from the “official report” published by judges in the wake of questions following the trial.

This court transcript does not even refer to a trial of Denmark Vesey, for example, but only a questioning of other witnesses and a determination that Vesey and five slaves were guilty of conspiracy. The witnesses, however, named people other than Vesey as the leader, offering no consensus that he headed up the plot.

Mr. Johnson concludes that white authorities may have framed Mr Vesey for several reasons, including the opportunity to shut down Morris Brown’s thriving AME church, of which Vesey was an important part. Johnson has said he believes that Denmark Vesey, as an outspoken freed man, was a logical choice to be made the ringleader. “My own take on this is: I think Denmark Vesey was a heretic at that time. He is a guy who thinks slavery is wrong, he hates white people, he thinks blacks should be equal to whites, and he won’t shut up about it. He’s endangering the black people and scaring the pants off the white people. And so he made himself a target.”

Governor Bennett protested the verdicts in his subsequent report to the legislature, objecting to the trials’ secrecy, convictions based on secret testimony, and the lack of an opportunity for the accused to face their accusers. He suggested that the testimony was “the offspring of treachery or revenge, and the hope of immunity.”

Responding to this and other public criticism, including by a justice of the US Supreme Court, the court, Johnson posits, arrested eighty-two more “suspects,” took more testimony about a planned slave rebellion, and executed twenty-nine more men. These actions solidified the idea in the popular mind that there had been a massive conspiracy to be defended against.

After the executions, James Hamilton Jr. was elected to Congress where he served in the House for seven years. He was elected South Carolina’s governor in 1830, leading arguments for “nullification”: states’ rights to declare any Federal law they considered unconstitutional null and void.

Mr. Johnson’s theories have served to deepen the controversy that surrounds Vesey, changing the question for some from “Was Denmark Vesey a freedom fighter or a terrorist?” to “Was Denmark Vesey a freedom fighter, a terrorist, or an innocent victim?”

Henry Darby’s feelings about Mr Vesey remain unchanged, perhaps even solidified. “I sort of resent when revisionist historians rely on old information to try to bring about something new,” he says, and cites the work of another historian, Richard Wade, who posited ideas similar to Johnson’s in the 1960s. Mr. Johnson, Mr. Darby believes, “is not bringing anything new to the field … he seems to be trying to galvanise people.”

The point, to Mr. Darby and others, is that the historical record is so flimsy that the truth is unlikely ever to be known, yet, Mr. Darby says, the notion that Mr Vesey and others organised a huge rebellion “seems empirically to be true.”

Mr. Johnson has said that he believes Charleston should, in fact, memorialise Mr Vesey, not because he was a freedom fighter, but because “he evidently believed that slavery was wrong and that blacks should be equal to whites,” and because he was the victim of a “vicious legalised murder.”

Mr. Darby says that although he believes Mr Vesey did plot rebellion, it doesn’t matter: “Whether one looks at him as a freedom fighter or as a victim, the fact remains that he was a black man who hated slavery and was executed for a cause.”

Joe Riley, the current mayor of Charleston, has called Mr Vesey “a significant figure in the long span of the civil rights movement.” “There are different sides to the story,” Mr Riley has said, “But in any event, he was a free black man trying to help enslaved Africans and it cost him his life. A monument to him is very important.”